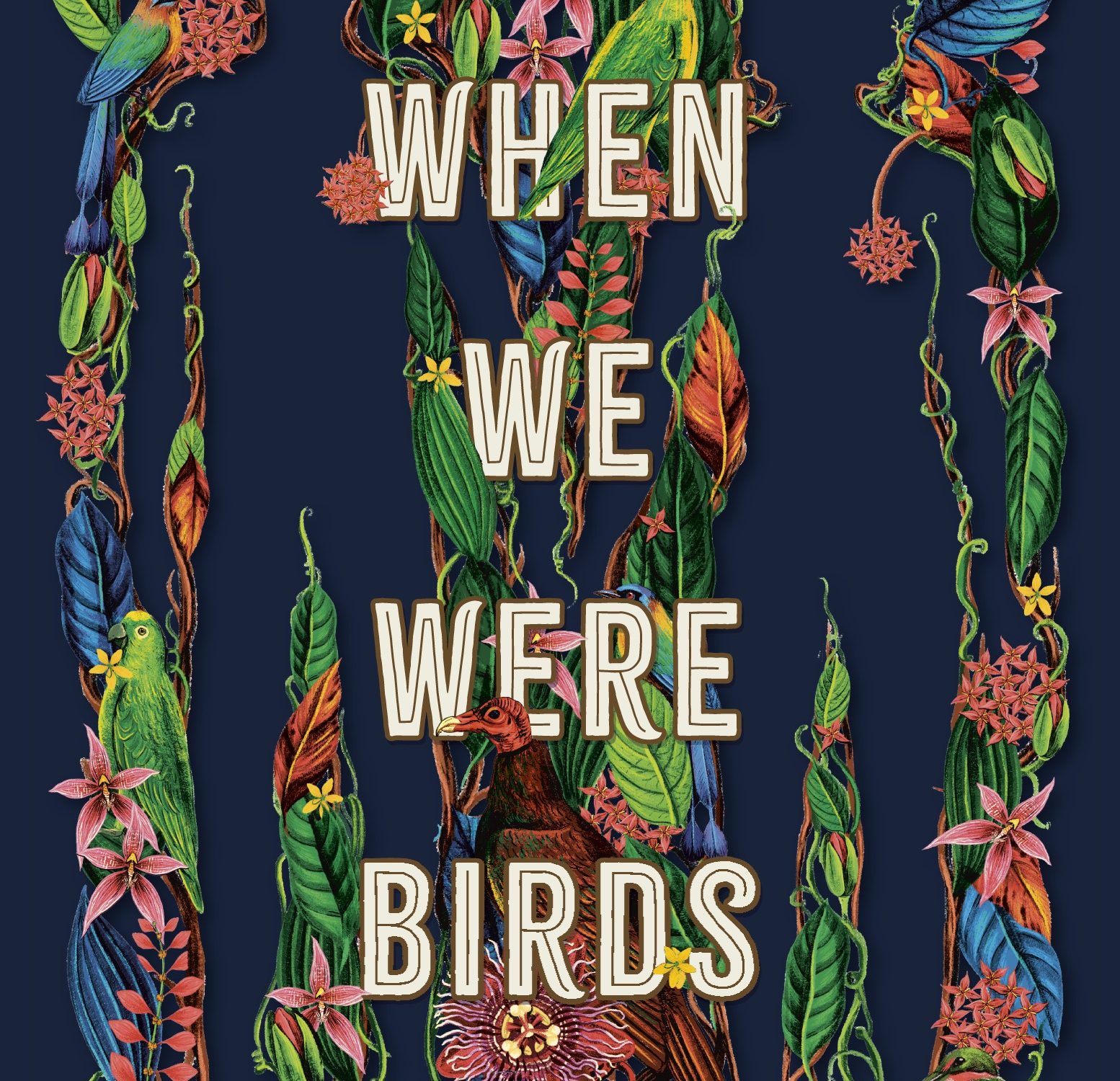

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

(Penguin Books, ISBN 9780593313619, 304pp)

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo, winner of the 2023 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, is an urban love-story, a story of love that is spiritual and predestined but also forbidden, a story of soulmates defying the rotted and crumbling structures of their inherited worlds. As the female protagonist, Yejide St Bernard, ponders, how do you tell your people “that you see a man somewhere in a dream and know you have business with him, and he have business with you”? For that kind of love-business, long-held vows of tradition, religion and familial obligation will be broken, pariahs embraced, by her and by the male protagonist, Emmanuel Darwin (he is “Emmanuel”, the saviour with us, and he is also Darwinian in his evolution from Rastafari to baldhead, son to self).

What makes this love-story even more poignant is that it is a case of “love in the cemetery”, as calypsonian, Lord Kitchener, once sang. Darwin is a gravedigger in the large, ancient and carefully laid out Fidelis cemetery. That’s where he first sees Yejide in a vision, that’s where her family’s plot is, that’s where her mother will be buried. However, Fidelis exists within the belly of a larger “cemetery”, the city of Port Angeles (a thinly-veiled reference to Trinidad’s capital city, Port of Spain) where corbeaux continually soar overhead while citizens drop dead below. City is cemetery, and cemetery is city. The bird-women, Yejide’s people, watch over the entire ecosystem with a supernatural power which has been passed down from mother to daughter for as long as anyone can remember. But the benefit of this power is also a burden to the St. Bernard women, and to the men who love them. Yejide is next in line and must decide whether to “end it now and she could be free. Nothing passed on. Nothing tying her to the women who came before.” Should she take her man and run, as she is advised to do? Can the dead learn how to stay dead, how to take care of themselves without a St Bernard woman to keep them company?

Death is a prevailing force in the world of this novel. For readers, like me, who don’t attend funerals, who stolidly avoid contemplating death and are made uncomfortable by the discussion of it, this book might be a difficult one at first approach. These pages engage openly and even jubilantly with the concept of death, its meaning, its rituals and with ways of grieving. However, I soon realized that the great triumph of this book is how balanced it is. The author masterfully paces and interweaves the birthing of new love, so as to counteract the darkness of the grave. In fact, I would go so far as to say that she makes the light combine with the dark to arrive at an ombré tone which is perfectly appropriate to the magical realism of this ghost story.

The bird-women, Yejide’s people, watch over the entire ecosystem with a supernatural power which has been passed down from mother to daughter

Oh and I believe it is very realistic (take it from me, a writer who has been both lauded and criticised for portraying an über-realistic Trinidad). This novel teems with so many interactions that are germane to everyday urban life here. The author’s eye for detail is obvious in her meticulous charting of the city’s landscape. Her dialogue rings true and she evinces a gift for choosing just the right gesture or turn of phrase to convey great swathes of meaning as her characters converse. She’s gotten the cadence and register of contemporary urban Trinidad creole just right. She’s gotten our dark sense of humour just right, too, causing belly-laughs at intervals, lightening the dark.

I wrestled, though, with trying to determine the exact nature of the power held by the bird-women. What exactly do they do? Their powers remain amorphous and undefined in my mind. This space of mystery both enhances and detracts from the sense of power. Yet, it almost doesn’t matter: the writer has still managed to achieve that “suspension of disbelief” in the reader, which is integral to the success of any story. With skillful writing like this, I would follow her anywhere. There is a luxurious mouth-feel to the prose, like a sip of ponche de crème on Christmas morning – a sweet, spicy, silky, slow-burning intoxication. There are no throwaway sentences, there is only flow. I can tell that Lloyd-Banwo loves these characters, has lived with them a long time, knows their mannerisms and idiosyncrasies. To her they are family.

One of the best books I’ve read in a long time. There were many instances where I had to stop, underline, and exclaim

Meanwhile, the avid reader of West Indian literature will encounter something rare and refreshing in this book: a house full of wholesome males who have willingly subordinated themselves to their women – and who boast about it. Yet, the writer in me found myself wanting just a bit less assurance, a bit more interior conflict in men like Mr Homer. The closest we come is when Yejide silently ponders “if Peter ration his own heart, loving just enough so he have something left for himself when Petronella up an leave, just so when the storm decide it was time”. This is a question I would’ve liked to see Peter wrestle with and answer for himself. But perhaps Emmanuel is meant to be that struggle personified.

Notwithstanding these minor queries, When We Were Birds is one of the best books I’ve read in a long time. There were many instances where I had to stop, underline, and exclaim, “Jah know! I wish I had written this line.” The driving scene, along the Northern Range put me in the backseat of the car with Yejide and Darwin, gripping my seatbelt, but also straining to hear what they were whispering to each other. My favourite moment, though, was, despite my aversions to all things death, the wake, beginning with the family’s recitation of the ways of dying of their ancestors, which had me both laughing and crying. In my opinion, that’s the high watermark of accomplished writing: immersion of the reader to the point where simultaneous conflicting emotions flow forth, inexplicably, just as they do in real life.

I just have to say this: Dearest Ayanna, congratulations, you have enriched the West Indian canon and, like Yejide, taken us all by storm.

∞

Celeste Mohammed‘s novel-in-stories Pleasantview won the 2022 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature.