∞

—

The symphony of words beckoned my hungry eyes and almost immediately giggles spilled forth. Words and strings-of-words screamed, sang, danced, played a familiar sweet sound: a sound of home, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The Vincentian twang was heard at the sight of: “Sin Vincent,” “een,” “mout,” “tek,” “e gimmie dis,” “arwe bring call ye.” Heard too were voices of Vincentian immigrants, who mimicked the British accent, but their subject and verb agreements were bitterly at war — “we smiles,” “we thinks,” we also reads, people calls, and we drinks. Vibes of friendship and love emanating from a melting pot of mid-20th century Caribbean migrants living the “Big City” life in London were felt too.

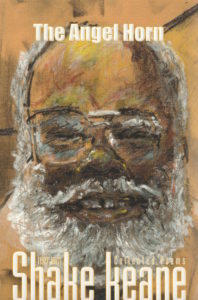

The Angel Horn – Shake Keane (1927-1997) Collected Poems is an anthology of six previously unpublished manuscripts of Keane’s poetry. Well into the first chapter, “Book One – Smiles in the Heart of the Family,” one gets a palpable sense of enjoyment, even of being amused or finessed by an “iconoclastic” wordsmith, a master storyteller, an innovative musician. That is when I paused and pondered.

Why the hell have I never read the work of this Vincentian poet before?

Why isn’t The Angel Horn used as a literature text for Vincentian students?

I then plunged again into the poetic paradise on paper. The chapters or “books” account for over forty years of writing in Kingstown, London, and end in New York City, where Keane lived until his death in 1997. Along the way, lyrical poems were dedicated to St. Vincent (“Barrouallie Dawn”), the Caribbean (“Three Roofs in Roseau”), and in “Book Six – Brooklyn Themes” to “friends at the Tiffany’s Lounge” (p. 163).

Quite the commander, Ellsworth McGranahan “Shake” Keane used words as his playthings to evoke and provoke reactions varying from joviality, to anger, to shock. The reader is pitched about on an erratic rhythm of verses evoking and provoking laughter, empathy, wisdom, sorrow, hypocrisy, tragedy.

Keane’s anger rises in “Credential” (p. 89), when his neighbours, girlfriend, and British nationals opine about his music, “all dis trumpit is a famous load o’ piss.” So vexed was he that he issued curse words, which he disappointingly swaddled in silly symbols in the poem. In “Barrouallie Dawn” (p. 55), wisdom prevails where, “The best staircases are spiral. For to venture/Upward or downward is to venture in many directions.”

In “Mistress Mucket’s Funeral” (p. 29), a virtual musical theatre piece set in St. Vincent in 1950, the reader lands in a crowd of wailing mourners at a Spiritual Baptist dance to the grave, to lay to rest a priestess. Decades later, it’s “Love in Bed/Stuy — Brooklyn” (p. 172), and the reader is taken to a holy church, then an unholy basement bedroom of a pastor who impregnated a church sister and then disowned her unborn child. She killed him during the sacred/sinful sexual act. The drowning of loved ones due to hurricane rains is a heart-aching exploration of loss in “Three Roofs in Roseau” (p. 44).

The unadulterated shock from a description of St. Vincent in the HARD-hitting “Book Three – Thirteen Studies in Home Economics” compelled me to do a double take:

one hundred and fifty square miles, providing us with

thousands and thousands of digging space acreage –

fertile and well soaked — capable of producing anything

except principles. (p. 77)

On the second read it felt as if my senses were derailed into near speechlessness; a low, slow “fuck” escaped my lips. Timelessness smiled its weary soul; with eyes closed I imagined the giant poet whining while blowing his trumpet to a sweet calypso, jampacked with political lyrics.

The Angel Horn poet blew themes of love too. Keane loved love! He passionately loved his “Angel Horn” (p. 181). The title poem is the book’s epilogue but from early on, love moved the poet. In “One Woman” (p. 67), it is “But only but ONE ONE Woman/And da’s M Y M O T H E R.” Among the women mentioned between the pages of verse, the women Shake Keane loved are Margaret, Zitrea, Ruth, and the women in Chateaubelair, Barrouallie, and Sion Hill.

He loved hopelessly. “Hardly a day passes/that I do not regret/having told you/how much I love you” (“Palm and Octopus,” p. 121). Furthermore, “I swear I have dreamed how/to touch you with my love” (“And Will You,” p. 119). For him “Love is strong beyond all things” (“Love Story (2),” p. 42). There is the sexual imagery where “Male frogs/live upon the backs of female frogs” (“Frogs,” p. 122). He even compared sex to the installation of a gun in “Love Story (21)” (p. 71).

The poet also connects love with death, “Knowing we shall die together/at our appointed time” (“Singing This Morning,” p. 118); “So they died/Telling each other secrets they already knew” (“Finding,” p. 51); death from a natural disaster “like love/like memory/is/always understated” in “Three Roofs in Roseau” and in “Love Story (2)” we are reminded, “For love and life and the moon can be broken/beyond all things.” Such connections of love with death evoke questions of Keane’s spirituality and belief in God. At times, the poet seemed irreverent in relation to religion. In a mother’s wail, he referred to “unclean Jesus” (“Public Prayer,” p. 33) and in “Here Am I Send Me” the comparison is to “a bat/hangs/between/the nipple/and/the left ventricle/lice/all over the bird in the ice — box/white/like/jesuschrist/ice/on/my/wing” (p. 93).

Inserted between minor themes and the heaviness of love, death, and religion, is the lightness of melodious nonsense. Keane wrote the sweetest “nonsense.” Lots of it! A nonsense found in the hilarious and touching ballad-like “Roundtrip,” is “bout this bermuda feller/how when he first see snow in New York/how he run outside and bring back a handful/put it in the frying pan and fry it/just so” (p. 10).

Shake Keane was a master of the art of “nonsense,” much of which was wrapped in Vincentian creole, which is still called, derisively, “bad talk.” His “nonsense” effectively conveys oral traditions and folk stories. Taken at surface value, some poems appear as absolute foolishness. However, Keane forces, or finesses the reader to pick sense from the nonsense, especially when he drew thin lines between the two. For example, “Hide and Seek” (p. 16) seems to be a silly song or game. However, skillfully inserted into the lyrics are significant snippets of Vincentian history, such as the war between the heroic Carib Chief Chatoyer and the invading British, and the influence of the colonial French on Vincentian culture.

Similarly, “Book Three – Thirteen Studies in Home Economics,” basically a long poem, forces meaning beyond the superficiality of surface nonsense to thought-provoking mathematical lessons. In “(Lesson Two: Options)” a manicou is used to highlight laziness. The nursery rhyme, “Ten green bottles standing on a wall” in “(Lesson Thirteen: Song of the Underdeveloped Casino),” makes comedy of the sad reality of women who serve as baby-making machinery for a multiplicity of men.

The structure of poems is another significant facet in a reading of Keane. The poet’s use of what may be called “shape poetry” to concretely project the creole speech or voice is seen in “Unu Coonoomoonoo” (p. 19) and “Apartite” (p. 22). The shapes draw attention to text and give a feel for and provide authenticity of the language and the reality of both Vincentian culture and an essential Caribbean-ness. In “Private Prayer” (p. 15), Keane reflects on the inherent versus the acquisition of language: “Why I don’t dream/In the same language I live in.” His flair with words may just be indicative of both aspects.

As we journey through his “books” the beat of Keane’s poetry changes from erratic to reflective. At the end of The Angel Horn, I too was thrown into throes of reflectiveness, particularly regarding language. The Vincentian creole remains largely scorned and considered as rural “bad talk.” (Ironically, today other vernacular languages are considered “cute,” notably the Jamaican patois.) Yet in the hands of Keane, the sophistication of concepts, the mastery of writing, and its delivery in verse all spiral up brilliantly, at times painfully, from the forge of Vincentian creole.

It is tempting to place language as the backdrop of “his frustration on his return home” (p. xi) from England and “self-imposed exile in New York.” What else could Keane mean with “The Islands (A Toast)” (p. 178), the last poem of the book’s final chapter? In this sort of a last stand declaration, the once strapping giant of a man (6.4 ft) — now aging, “a small knife” in his “withering” hand — makes a damning link about the deterioration of health, loss among “our tribe,” and death itself, to the refusal, the inability, the not knowing about how to live one’s identity in one’s own language: “St. Vincent, for example/…/Cannot protect, digest, cannot interpret its own ….” But there are worlds of salvation to discover in this “fifth and most comprehensive book of Keane’s poetic range and vision from the late 1940s to his last poem written in 1997” (p. 184).

Shake Keane was undoubtedly a visionary, a legendary poetic genius of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. His publisher, HNP, reminds us in the book that Keane remains “One of the innovative fathers of Caribbean literature.” My poetic journey through the nearly 200 pages of The Angel Horn was absolutely fascinating and completely satisfying. But, like a she-devil lover, I looked at Shake Keane’s photograph on the cover and whispered … done already?

∞

N.C. Marks (Natasha C. Marks) is a writer from St. Vincent and the Grenadines. She attended the the University of London and teaches geography at the St. Vincent Girls’ High School in her Caribbean homeland.