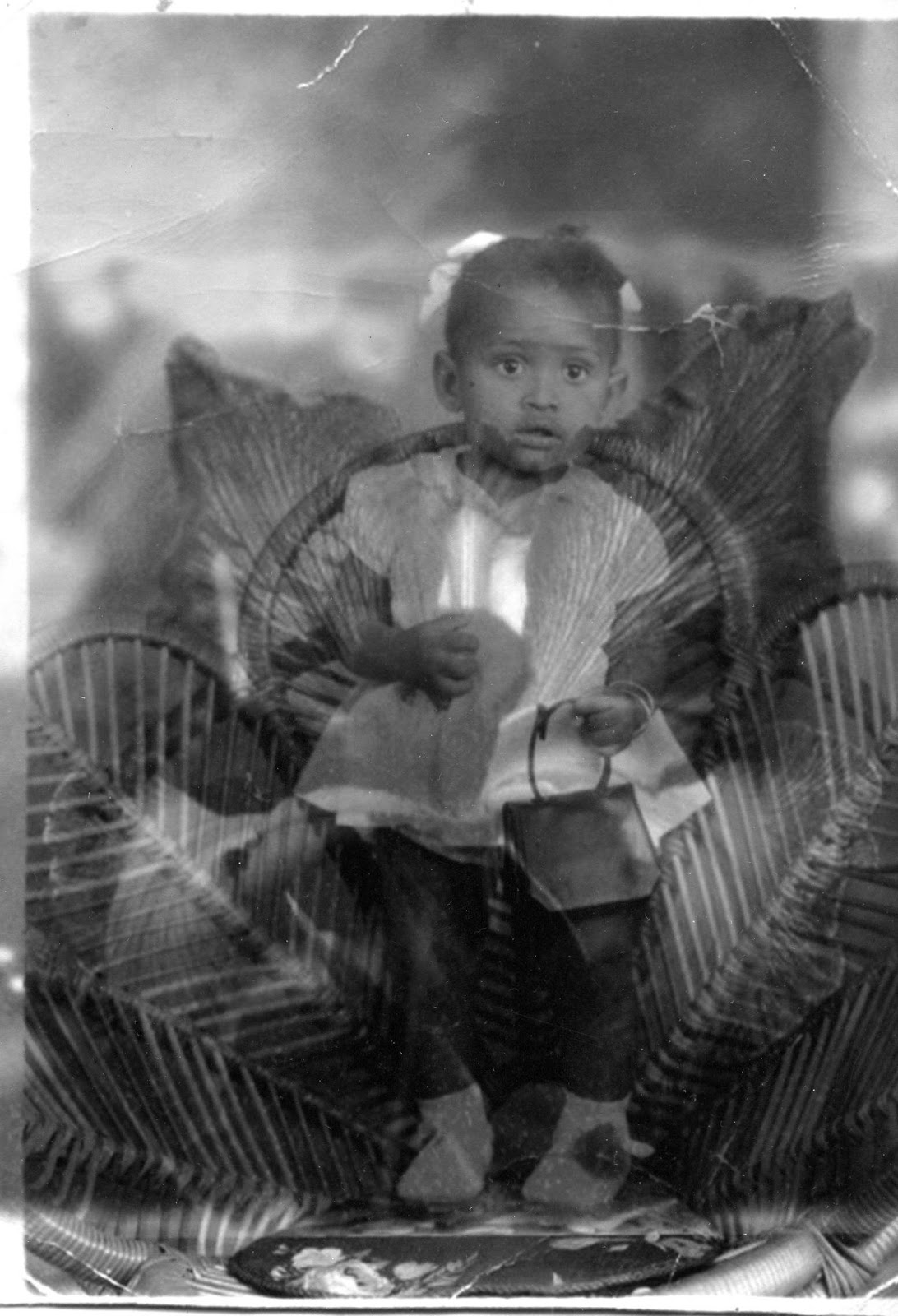

Image Courtesy of Jacqueline Bishop.

—-

As long as I can remember, my grandmother has kept photographs in a jumble around her, and whether my grandmother is aware of it or not, the photographs that she has, and where she places them, gives a pretty accurate picture, to my mind, of where she places people in her life. Her dresser for example, is full of photographs of a great grandchild that she adores, and those of us who are fortunate enough to be in her favorite category end up in her big black Bible.

As a child living with my grandmother I quickly learnt that there were photographs that I was not to touch. These were the ones carefully stored away in the clear plastic bags that would eventually ruin them by becoming hot and sticky and the photographs peeling. These were different from the pictures pushed into the sides of the large oval-shaped mirrors on the cabinet or dresser that we could take down and handle, though we should be careful not to leave any fingerprints on them. The really precious images were framed, of course, the wedding pictures, for example, and these you would find prominently placed on the mantelpieces of both my grandmother and my great grandmother’s houses. Sometimes there were images that haunted, of a family member who died young; and there were the ones I was simultaneously repulsed by and drawn to, the images of people in coffins, for example. And then there are the strange images of “Chinese people” that are all over my grandmother’s house, that only recently my grandmother told me were people she used to work for years and years ago. I wanted to ask her about these Chinese people, my grandmother, why she felt the need to keep and display images of people she had not seen in decades, but I suspect my grandmother has grown both leery and weary of me and my questions so I do not push the issue.

***

Her home. My grandmother’s home. As I look back at it now I see that my grandmother, as her mother before her, use photographs as a means to keep people that have moved far away, close to her. My grandmother, as did her mother before her, uses photographs as a means of holding onto something she fears may slip her grasp, and this, of course, makes sense for people who have watched children, grandchildren and even great grandchildren move away in successive migrations, not knowing if nor when they will ever see these loved ones again. My great grandmother, for example, would sometimes take up the photographs of her daughter and her daughter’s children then living in far away England, and she would speak to herself in a slow sad whisper, her voice thick with tears, wondering if she would ever see her daughter again? Wondering if she would ever see those beloved grandchildren again? Then my great grandmother, Celeste, would go out to stand on the verandah facing the dark blue Portland mountains, some of the pictures in her hand, and you could hear her calling out every last one of her daughter’s children’s names.

I sometimes think that it was because my great grandmother never knew her own mother, who died when she, my great grandmother, was but a year and a few months old, why my great grandmother and grandmother and now me, their great granddaughter, have all been fascinated with photographs. She once said to me, when we were walking somewhere and talking, my great grandmother and I, “Eh, can you imagine it Jacqueline. Not knowing what your own mother look like? Not having even one teeny-weeny picture of what your mother look like? Having to rely on other people pointing out other people to you for you to know what your own mother look like. Can you imagine such a thing?”

It is a predicament of many black people.

***

For a long time the small photograph towered above me. The small framed photograph of a girl I do not know, but do know, who lived above the cabinet in my grandmother’s house. Every time I went to my grandmother’s house I would look up to make sure she was still there, the girl I do not know but do know, the one standing on the chair with the back like a fan, the girl in the pale dress, pale shoes and had big pale ribbons in her hair, the girl, staring out as if she was about to cry. Who had taken her to have the photograph taken? It must have been her mother — for the me who is in the photograph became transposed as a “her”. I can see it all unfolding in my mind’s eye. My mother would have gotten up early that morning, knowing for days if not weeks ahead that this would be the day when she would take me to have my baby photograph taken, for everyone got a baby photograph taken in a studio. Probably she had picked out the white clothes I was to wear the night before, my mother, knowing, or having been told, that white clothes would show up lovely in black and white photographs. She would have bathed me, my mother, lovingly combed my hair, and she would have put the two big white ribbons in my hair.

Then it would be off to the photographer’s studio in downtown Kingston. By the time we got to the studio, this or that thing might have come out of place, and so my mother would have reached into her bag for the brush or comb she would have carried with her, and she would have brushed my hair back in place, and straightened out my ribbons. She would have done everything she could do, my mother, to have the photograph come out just right. The photographer would then place me on his spreading chair and then the two of them would again set to work straightening out my dress, fixing the bangles on my hand, making sure that my socks were neatly turned down. Together they would try to get me to smile, and when talking to me did not work, they would have started dangling something in front of me, let it be something strange, from the look in my eyes — something I have never quite seen before (maybe the camera) — because I am convinced that if it was something nice and bright and shiny I would have been reaching for it.

As I look back on this image I am struck by the fragility and vulnerability of this image. Maybe the size of the size of the photograph (at just about 3×5 inches) or maybe the fact that the image is black and white is what adds to the fragility and innocence of it all. The frightened yet vacant look in my eyes.

In some ways what draws me most to this image is the small black handbag that I am grasping tightly in my left hand. Family lore has it that as a very young child I would watch my mother get dressed, pick up her handbag and leave the house and one day I did exactly the same thing without anyone knowing. I was found at a busy intersection about to step off into the street. After people had gotten over what could have possibly happened to me … if, Lord Jesus, if the child done stepped off into the road … they would then come back to this small black handbag and how tightly I held it, as if I was a little woman going to work. As if, even then, I liked having my own-way.

It is a strange thing looking back on yourself as an infant, looking back at another you in a sense, a you you do not know, for even as I know the little girl in the photograph has my eyes, my lips, my face, I feel as if I don’t quite know this little girl in ways that I feel as if I know the little girls in my ten year old photographs for example. I am still on speaking terms with some of those ten and twelve year old girls, whereas I have absolutely no recollection of the little girl who went off in her pretty white dress to have her picture taken. Yet, I feel instinctively protective of her, want oftentimes to reach out and touch her. I often use this photograph as a measure between the child that is in the photograph and the woman who is writing about the child in the photograph today.

I have always wanted to own this photograph.

And so, one time, when my grandmother left the island to spend a few years living in Canada with her daughter, and there was no one around to tend to the photographs on her mantelpiece, I finally got my hands on the photograph that I had always coveted. For the longest time I would just look at the photograph, on my mantelpiece in New York City, and just be happy I had her and I was carrying on in my grandmother’s and great grandmother’s footsteps. But as the years went by and I began to delve deeper and deeper into the visual arts, I started making various iterations of this photograph, and I would laugh and say, wow, the child in this photograph is such an immigrant, migrating from one image to another. Most recently I added a flower within the center of the image and carefully modulated the light and dark shades so it seems as though the child is a flower is a child and it is hard to separate the images. The image then became part of a larger discussion about childhood memories that I have been working on for several years now.

Most days when I look at this photograph I stole from my grandmother’s house so many years ago I smile at the little girl with the big white ribbons in her hair and reach out to take her hand. Her sister image, the one with the flower, the one that also sits on my mantelpiece in New York is often quick to remind me that not only have I become my grandmother and my great grandmother by keeping photographs on mantelpieces in my home, but that the mantelpiece that she is sitting on in New York, is not the mantelpiece where she belongs. Her place, the girl in the photograph in New York insists, is in Jamaica, in a small district called Nonsuch, high in the blue Portland mountains.

That first photograph, the original, the untouched digitized version without the beautiful flower in the center, speaks of being in exile, in a far away and sometimes brutally cold New York, and that she really belongs with a woman named Emma, the pictures all over Emma’s house, the mantelpiece where she should be sitting; that is the place where she really belongs.

—-

Jacqueline Bishop was born in Kingston, Jamaica. She currently teaches at New York University, where she earned her M.A. in English & American Literature, and her M.F.A. in fiction writing. She has been awarded a UNESCO/Fulbright fellowship, The Arthur Schomburg Award for Excellence in the Humanities, and five Jamaica Cultural Development Commission awards, among many other honors. Her work explores issues of home, ancestry, family, connectivity and belonging.