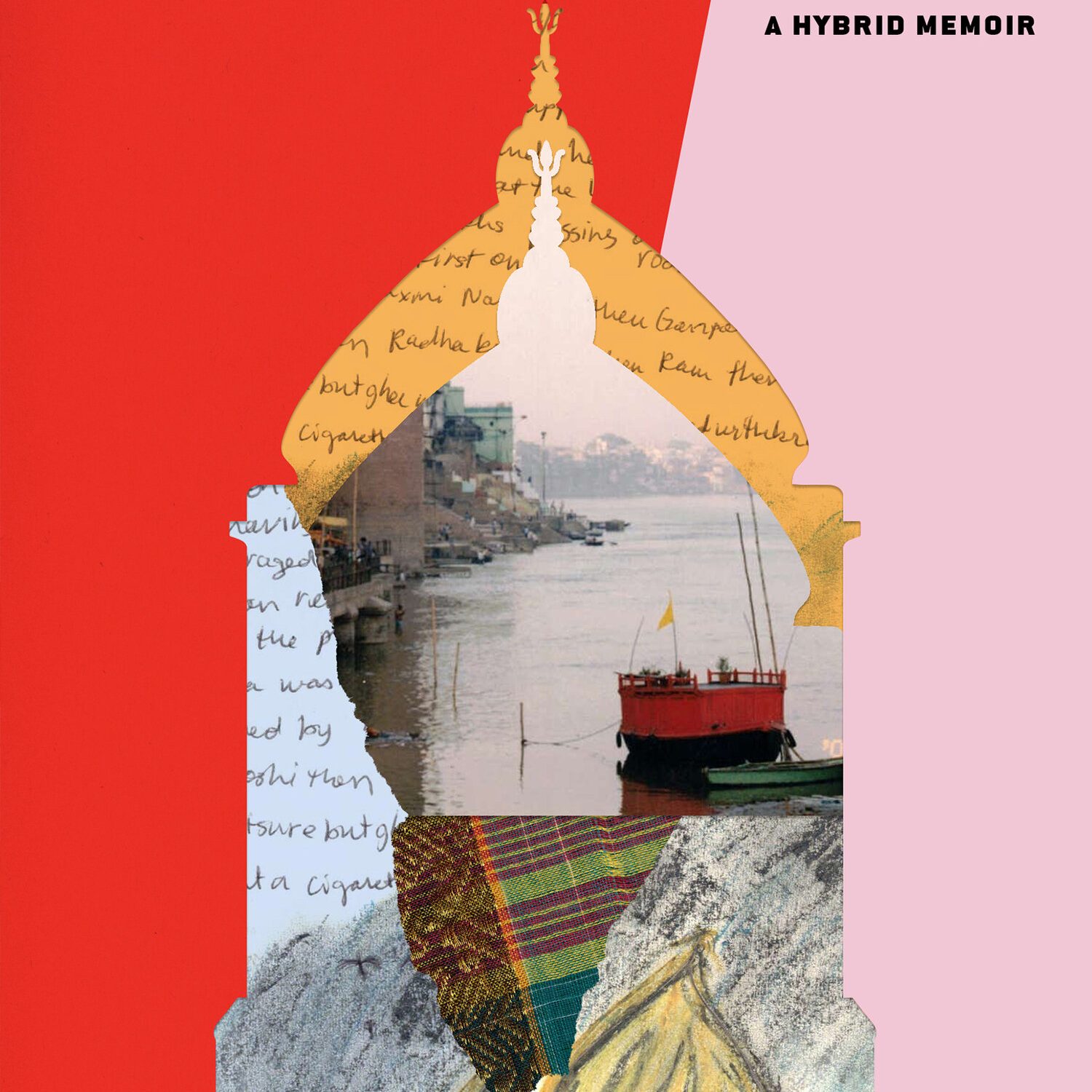

Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir by Rajiv Mohabir

(Restless Books, ISBN 9781632062802, 354 pp)

When I first observed the title of Rajiv Mohabir’s upcoming memoir, Antiman, I had no idea what it was in reference to. I simply thought of it as a cool word with possible Marxist meanings, and then went back to thinking about other things. Luckily for myself and many readers outside of the Caribbean, Mohabir clarifies it in his author’s note. An antiman is an English Caribbean slur for homosexual. Think auntie-man, with a West Indies lilt. I still think the etymological slant of the word serves the title, ie the anti-man.

Antiman the memoir concentrates on how Mohabir’s lingering identities, from the Bhojpuri songs his grandmother sings to the homophobia of his Indo-Guyanese community, imprison a man who was otherwise born and raised outside of the shackles of these concepts. In many ways, Mohabir’s placement into this world has made him into everything that people of his context must go against. He is too brown in the United States, too gay for Guyanese people, too NRI (Non-Resident Indian) for Indians. He is ante man: not yet afforded full status. And yet despite being completely outside of the box, Mohabir finds ways to not give into the negativity. He is not merely an antiman, or auntie man, or ante man, or even anti-man (these word associations are made by Mohabir in the preface). He can give space for himself and for many others who also live in the matrixes of complex identity.

The triumphs of Antiman are more than identity-related. Antiman is compiled structurally as a collection of personal narrative, poem, alternate ending sequences – even one chapter is told as a lesson plan. Inside of these motifs are variations that remain consistent. Whenever a narrative is entitled an ‘Aji Recording,’ it is meant to involve language framed through Aji’s perspective, either through song, or verse, or confession. The section will most often be written in Guyanese Creole mixed with Guyanese Bhojpuri, though Mohabir sometimes subverts our expectations.

All of Mohabir’s virtuosities are on display in Antiman. The criss-crossing between languages and narrative structures, the blurring of linguistic and national lines, as well as the pathos Mohabir builds for one particular life raised in suburban Florida.

The titles also often act as a clue to the structure that the individual chapter will most likely take. ‘Ardhanarishvaram Raga’ at first appears to be a translation of a raga, with Devanagari writing on one side, English on the other. The language suddenly loosens. The Devanagari script disappears, to be replaced by Guyanese Creole. A raga was not being transliterated, but subverted through Mohabir’s mastery of various tongues. ‘Mister Javier’s Lesson Plan’ involves Mohabir reacting and responding to his Latin American students in New York City. Mohabir struggles to adapt to them, and in many ways they struggle to understand him, and that misunderstanding is brought up in the sequential form of a lesson plan.

Conversely, ‘A Family Outing, Alternative Ending’ uses three different outcomes to imagine how Mohabir’s family in Canada respond to a Tamilian partner Mohabir brings to their New York family home. Each of the fictional stories is told in third person omniscient narrative, outfitted with a different style to match the visuals of the outcome. Alternative Ending 1 is the most dramatic, and so the sentences are effusive and emotional. Alternative Ending 2 has a more meditative paragraph structure, befitting the more vise and objective stance the characters take. Alternative 3 has the most terse and staccato style.

To include fiction and poetry in a memoir is already a structural challenge, but Mohabir is not only willing to play with the blurring of genres; he is willing to take risks in the storytelling and structural decisions embedded in each of those genres so that his writing can come that much closer to revealing his truth.

And what is that truth, in fact? At the heart of it all, Antiman is an ode to the family. The memoir begins rooted in Mohabir’s experiences with his grandmother. Mohabir feels a deep connection to his Aji, and from their relationship he develops a passion for Bhojpuri song, Guyanese tradition, and North Indian culture. At the same time, because Mohabir also is gay, and was raised in the United States, his ability to fully connect with his heritage is limited. His extended family openly mocks him and belittles him, his father struggles to see any values in his life decisions.

And yet, Mohabir persists to learn Hindustani, Mohabir travels across Uttar Pradesh to find his grandmother’s hometown, Mohabir dates men from all across the subcontinent. Because no matter what the outside world says, Mohabir gravitates towards South Asia and its cultures. And it is in this passion and pride for his motherlands that he ultimately finds that he truly belongs.

All of Mohabir’s virtuosities are on display in Antiman. The criss-crossing between languages and narrative structures, the blurring of linguistic and national lines, as well as the pathos Mohabir builds for one particular life raised in suburban Florida. What makes Antiman more than required reading for our time and age is not merely how many boundaries are intersected in Mohabir’s memoir. It is his conviction to innovate in style and structure no matter how familiar the story being told remains, and to highlight not merely one man’s struggle for recognition despite his differences, but his desire to give voice to a diverse microcosm – the Indo-Guyanese community of the United States – addressing erasures on the international stage.

∞

Kiran Bhat has had reviews published at The Kenyon Review blog, The Brooklyn Rail, The Rumpus, Waxwing, and elsewhere. Born in Atlanta, Georgia, to parents from Southern Karnataka, in India, he has traveled to over 130 countries, lived in 18 different places, and speaks 12 languages, yet always finds himself centered around Mumbai. He is the author of the novel we of the forsaken world… (Iguana Books, 2020) and tweets @WeltgeistKiran