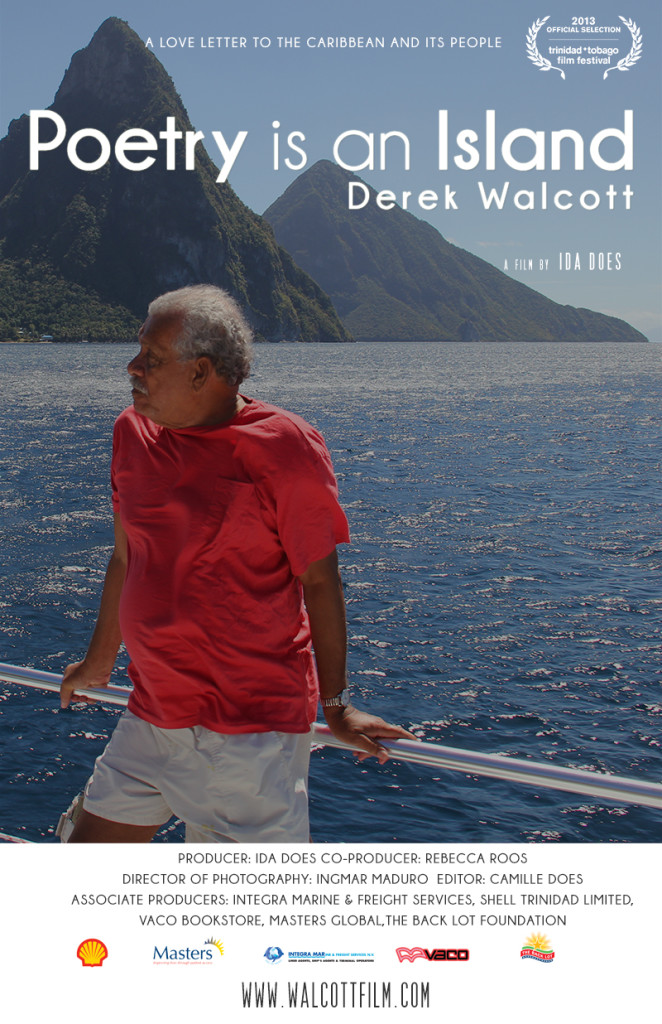

Towards the end of Poetry is an Island, the recent documentary film directed by Ida Does, Derek Walcott’s longtime friend Arthur Jacobs, an actor and dancer, says that as the great poet gets older he is coming to terms with his own mortality. Jacobs can’t imagine St. Lucia without Walcott, for it would be a dark place indeed. In one scene, Jacobs reads from poem “37” of Walcott’s collection White Egrets, a poem about none other than the actor/dancer himself. The camera captures the aging Jacobs shirtless, with arms and chest heavily covered in keloid scars, thick and sinuous like rivers on a map. Jacobs’s eyes water, and his voice breaks, so touched by the words, which Ida Does adapts in one magnanimous frame:

Arthur Jacobs, the bare pate, the broken teeth

that make his grin more powerful, a man with no money

despite his tremendous presence, light as a leaf

and as delicate dancing, coal-black and like coal

packed with inspiring fire, a diamond with its memory fading[.] (69)

Jacobs reads this passage as if he were reading from his prayer book or the Bible. Alone in his wooden house, surrounded by photographs of a past acting career framed and hanging on the walls, Jacobs strikes a figure in stark contrast to the 1992 Nobel in Literature. Whereas the eighty-five-year-old Walcott still possesses a razor-sharp memory, allowing him at so advanced an age to still put on plays, the same, unfortunately, cannot be said about Jacobs. The former leading man, who is unable to remember his lines, can no longer find work acting. The contrast between Jacobs in his home and Walcott on his estate is breathtaking in that it not only gives the viewer a perspective on how wealth and the concept of “success” is measured, but also nods towards Walcott’s humble origins, his roots. Remember: he and his family grew up in a house no different from Jacob’s, and Does makes sure this is not forgotten. But Jacob’s success—his legacy, if you will—is also celebrated. A brief two-second shot of a Certificate of Achievement—mounted—from a local theater group commending him on his dancing, draws the viewer closer to Jacobs; lifetime dedicated to the craft of acting will not go unnoticed. Does honors Jacobs because he represents St. Lucia as much as the Nobel Laureate.

The artist Dunstan St. Omer, called “Gregorias” in Walcott’s poems, reads from Part Two of Another Life in his interview with Does. He says, “I have been written about by a great man. So, I will live on forever as Poetry, myself and my family.” Unlike Jacobs, however, who reads poem “37” of his own accord, Does obligates St. Omer to read. Straining his weak, myopic eyes since he forgot his glasses, he takes his time to get comfortable reading. The scene of St. Omer modestly not wanting to read endears him to the viewer. He just wants to avoid tripping over a word and so, in his mind, failing to do justice to the poetry. A sampling of those lines in St. Omer’s raspy smoker’s voice is as follows:

all the Gregoriases

were pious, arrogant men,

of that first afternoon, when

Gregorias ushered me in there,

I recall an air of bugled orders,

cavalry charges of children

tumbling down the stair,

a bristling, courteous father[.] (191)

Having these two great St. Lucians read poems from two distinct stages in Walcott’s career does more for St. Lucia and for the poetry itself than to show scenes from Stockholm, Walcott rubbing shoulders with members of the Academy and Swedish nobility, and a voiceover of him giving the Nobel Lecture, “Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory,” in the background. Does presents the scene at Stockholm at the moment Walcott approaches the podium and addresses the Academy. Before reading from the lecture, however, he honors St. Lucia, its people, and the entire Caribbean by voicing that he receives the Nobel Prize on their behalf, and not solely on his. Does further heightens the experience for the viewer when she pans out to a scene depicting a Trinidadian field where a dramatic version of the great Hindu epic, The Ramayana, is being performed, thus nodding towards the opening of the lecture. Walcott articulates eloquently that The Iliad and The Odyssey are two Asian epics like The Ramayana. A masked actor portraying the ten-headed demon king Ravana and a massive statue of his giant brother Kumbhakarna, which is burned in effigy in the documentary, further dramatizes Does’s point. She also lifts a phrase from the lecture, using it as her title, Poetry Is an Island.

Interviews with the people closest to Walcott, who know the man and his work, and who speak casually about him and in an anecdotal way, are when Does’s film is at its strongest. Natalie La Porte, Walcott’s acting protégée and longtime student, and his assistant Michelle Serieux, who opens the documentary by saying he has “wandering eyes,” show sides of Walcott which aren’t necessarily expected of him. He is a lot more than just a poet, playwright, painter, and intellectual. Walcott, to paraphrase both women, is a man of great passions, a true lion. His eyes wander in that he is always exploring his environment, forever scrutinizing, for example, the St. Lucian landscape, and trying to discover ways to adapt that very scrutiny of reality and express it through works of art. One of the most revealing scenes has Walcott, fellow poet and 1995 Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney, his wife Marie Devlin, and West Indian novelist Robert Antoni all congregated at the Roseau Valley Church to see the exquisite mural painted by Dunstan St. Omer (Gregorias), which serves the church as altarpiece. Not long after the filming of the documentary Heaney, regrettably, passed away; St. Omer, Walcott’s childhood friend, an artist of great power and originality, also passed. In Does’s film we see two of the 20th-century’s leading poets together for the last time, talking about life, death, and how art reconciles the two. This is a gift beyond words.

Walcott reads the last movement of “Saint Lucie,” a poem in five parts, titled “For the Altarpiece of the Roseau Valley Church, St. Lucia.” His rich baritone resounds as it echoes off the church walls; we are completely immersed here in the oral tradition of poetry. Walcott’s voice transforms the imagery witnessed in the mural, especially the centerpiece, a lovely brown Virgin in a baby-blue robe cradling a brown Divine Child, cute and chubby. A section of the poem featured in the film follows:

The chapel, as a pivot of this valley,

round which whatever is rooted loosely turns—

men, women, ditches, the revolving fields

of bananas, the secondary roads—

draws all to it, to the altar

and the massive altarpiece,

like a dull mirror, life

repeated there,

the common life outside

and the other life it holds;

a good man made it. [emphasis added] (319)

“[A] good man made it,” Walcott’s says and it’s his way of reciprocating the love he received from Gregorias when St. Omer sayid he has been written about by “a great man.” Does skillfully combines Gregorias’s mural with Walcott’s ekphrastic poem, proving she understands that art produces more art. The conversation between Heaney and Walcott deals with how the mural and church intertwine and are inseparable; the very inseparability between the concepts of “art” and “faith” in turn creates a feeling which Heaney calls “The People’s House.” Thousands of miles away from his native Ireland, Heaney feels he is in “The People’s House” while visiting the Roseau Valley Church in St. Lucia, a feeling he would relish in certain sacred grounds in Ireland, meaning that the sensation is universal.

Walcott breaks down and cries when Does literally forces him to read the passage in Omeros in which he honors the memory of his beloved mother, Alix Walcott, she suffering from Alzheimer’s and he trying to (re)connect with her. “This is wicked,” Walcott says between sobs, trembling in his chair but soldiering on nonetheless. His pained, vulnerable reading engages the viewer all the more since Walcott is such a powerful, imposing presence. Does also captures Walcott crying during one of his famous birthday parties, a yearly event, in which famous writers, poets, publishers, and friends all meet on his estate overlooking the sea, not far from Soufrière and the Pitons. When he and his guests, who include Glyn Maxwell, Jonathan Galassi, Matteo Campagnoli, Nicola Crocetti, Christian Campbell, and again, Seamus Heaney and Robert Antoni, are asked to recite a couple of lines from a poem of their choosing, Walcott, on reciting, gently weeps.

He weeps because he has led a life that any artist, even an extraordinary one, would envy, and knows his life is winding down, a life of noble work, an illustrious career not only as a poet but as a dramatist and painter. Aside from Walcott the artist, Does’s film also shows us Walcott the activist, vehemently opposing the construction of a five-star hotel on the sacred ground of the Pitons. He insists that the development of infrastructure in the Caribbean shouldn’t model the “big cities” of the United States, Europe, Asia, and elsewhere, but should scale the construction (if not down) than according to the natural beauty of the Caribbean.

Does’s documentary is an honest portrayal of Walcott, his life and work. It shows the man amidst all his triumphs and yes, imperfections. In one scene, Jacobs says something truly intimate about Walcott: that if he could strap himself to a machine that would prolong his life for another fifty years he’d do it in a heartbeat.

Does’s documentary also shows Walcott furious that the St. Lucian government, on giving him his own personal island (Rat Island) as a place for poetry readings, theater, and international residencies, has literally gone to waste. Rat Island is completely abandoned and rundown. It also shows how hurt Walcott feels that nothing by way of commemoration has been done by the St. Lucian government for his late twin brother, Roderick Walcott, who is no less a man of letters than the more famous twin. Moments like this reveal the complexity and humanity of the great poet whose work, even if one were you to judge solely on the seventeen collections he has published so far, is unmatched, in any language, in its power and delicacy.

—-

Sharif El Gammal-Ortiz is a poet and translator from Carolina, Puerto Rico. His poetry has been featured in The Acentos Review, The Atlas Review, What I Am Not a Painter, Entasis Journal, SAND, and elsewhere. An essay and a book review are also forthcoming in The Caribbean Writer and Caribbean Studies, respectively. He is a doctoral candidate in Caribbean Literature at the University of Puerto Rico, Ri’o Piedras. His research interests include violence in the novels of Guadeloupean writer Maryse Conde’ and how it relates to the broader historical constructs of the Caribbean.