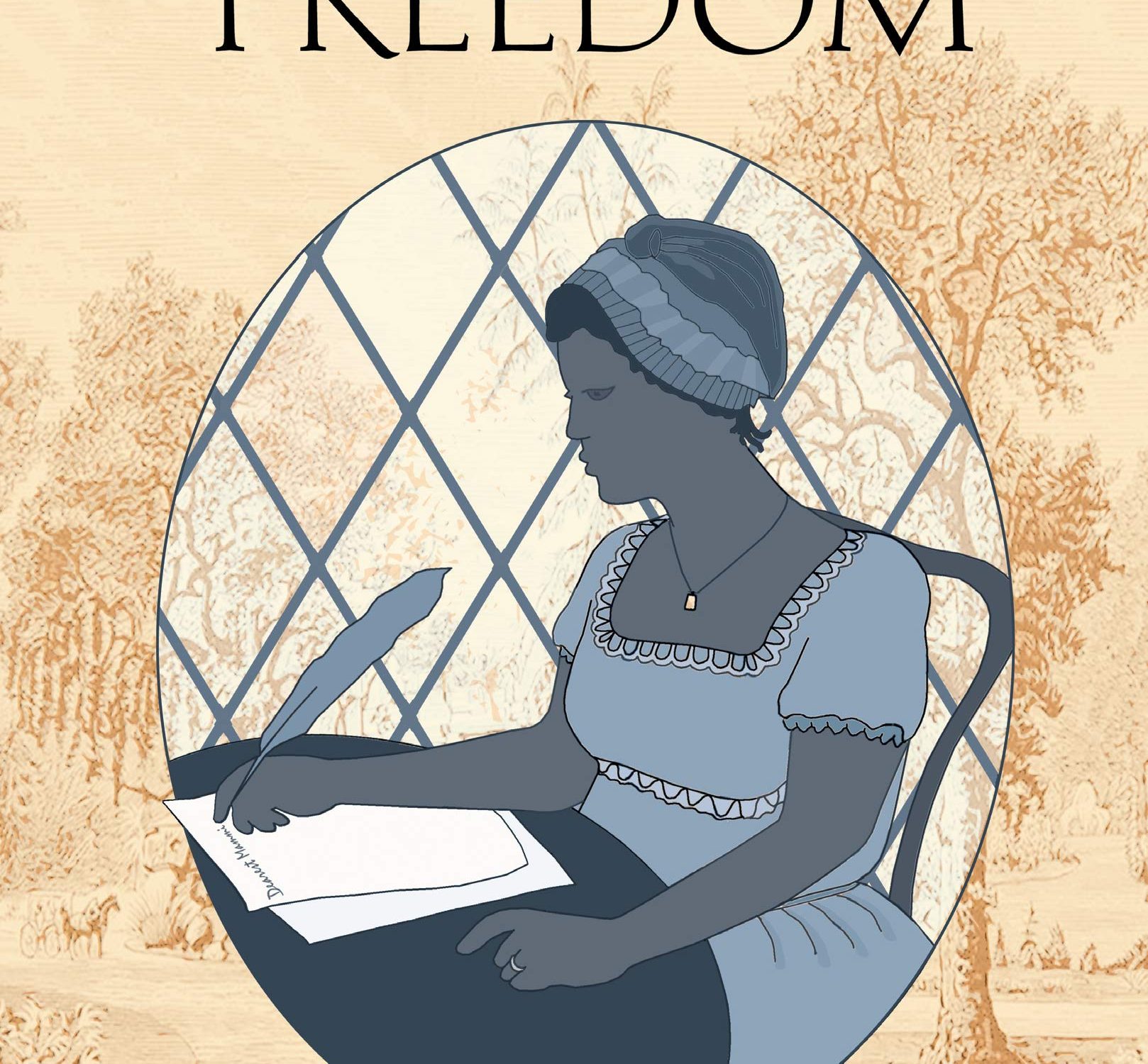

The 2013 British period drama film Belle brought the story of Dido Elizabeth Belle to new audiences all over the world, and award-winning Trinidadian novelist Lawrence Scott’s newest book Dangerous Freedom is poised to do the same. Weaving fact with fiction, the novel tells the story of Dido, who was the daughter of an African-born enslaved woman, Maria Belle, and the sea-faring nephew of Lord Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice of England. Dido has not heard from her mother for twenty-eight years and yearns to hear from her. Dido is now a married woman, Elizabeth d’Aviniere, remembering her past life.

“In Dangerous Freedom I am trying to redress what I see as the romantic portrayals of Dido in art, film and literature,” says Scott, who has made a name for himself with his historical fiction. “I wanted to question the sketchy history we have of Dido and, through fiction, to alter the psychological and political perspectives. I hope that the novel can add to our understanding of a pain that remains just below the surface of contemporary life.”

The novel was launched in March and is presently out in the UK and Trinidad (Paper Based Bookshop) and available in the US in June. Moko Magazine features the following extract courtesy the author and the book’s publisher, Papillote Press.

∞

At this time of her life Elizabeth d’Aviniere was living in a modest house on Ranelagh Street. It was the winter of 1802 and the last of autumn lingered in the fallen leaves. Another war was stirring. She felt that she was in a fortunate state, though not with all her freedoms. Many of those had been threatened or never given. But, nevertheless, she was satisfied now with her husband and her sons, and mostly occupied with her memories, which on evenings came gently, as evenings could.

She recalled when she was a small girl swaying in a hammock in a different climate with its brief sunset, her mother telling her the story of her life. Is four years since you born on your father ship. We up and down the islands. Remember the year, child, 1761. You go have to write it down one day. The ribbons of light then were mixed with the shadows on the pitch-pine floor of the porch. They swung to and fro in a silence filled with the breaking of the waves on the nearby shore and the scratching sound of palm branches in the breeze; a long long time ago, as her mother would say in her singsong voice. That was in Pensacola, the British port in Florida. It was a geography her father had taught Elizabeth with his maps, pointing to where he had bought her mother from the auction block and then put her in his house, which was on the front with the tall ships moored between the shore and Santa Rosa Island.

Light was different here on Ranelagh Street, not far from the banks of the River Thames where the creeks, water meadows and marshes lay just beyond the streets of Pimlico, choked in spring and summer with nettles. It had been her home for these last eight years. What was even more different now was her name, that she was called Elizabeth, or Lizzie, by her husband, John. He would keep to formalities in public, calling her Mrs d’Aviniere. But he called her Lizzie when he greeted her with kisses and cuddles, whispering, Lizzie, Lizzie, Lizzie darling, like a young lover. How sweet it was now to have his name in marriage, a proper surname, a real name, a free name, not that silly name, Dido, not that slave name. Her sons called her Mama. She was fortunate, she had to keep telling herself, despite the loss of her mother. Was she like Mr Olaudah Equiano, the African, a particular favourite of Heaven as that author’s narrative so elegantly described his circumstances? She hoped that her pen would work a similar magic in the telling of her tale.

Her mother’s voice was talking of rivers as Elizabeth settled down to write her story: far over there and so long. She traced the distances on her father’s map, which he had given her during one of his last visits, long ago when she was a child in London. She pressed out the creases where it lay upon the table, travelling with her fingers from the hinterland of the large continent to the coast where they had lived at that time. Is an eternity they take, oui, girl. She remembered her mother teaching her to pronounce the name Mis sis sip pi.

Elizabeth’s tongue had been straightened out to fit into England though she always felt that she had never quite achieved what was expected. People still turned and looked at her, even now, and sometimes asked her origin, though they could always see it plainly, she thought. This left her feeling uneasy.

Some of her more gentle memories and her mother’s stories of Pensacola were filled with names, just sounds now, like those of the birds that sang in the trees, Creek and Chickasaw, Choctaw and the name that made them laugh aloud, almost falling out of the hammock, Chief Cowkeeper. Her mother would go on to talk to her of the rivers: Apalachicola, Yazoo, Matanzas forming thoroughfares to reach the north by ship and canoe, paddling on and on. Far, far away, they say, her mother said. She had once asked her father if she might ever go there on a canoe. He had smiled as he often did, shaking his head, No, my pet, his favourite expression when talking to her then.

Elizabeth listened more intently when her mother started to tell a harder story.

We find them people here when we reach by boat and they drop the anchor in the harbour, we so exhausted, so starved and thirsty and not daring to think that we might step upon land again, them chains such a part of we limbs that not to have them shackled to each other, to our ankles and to the boards, don’t seem usual and ordinary at all when we come to stand upon the dry ground and have to walk, stumbling like we accustom on the deck of that terrible ship.

Elizabeth enjoyed making up her mother’s voice. She wrote it as she heard her speak. To find her on her tongue was to keep her close, to try it on the page was to keep her even closer and not to lose her, ever.

∞

Lawrence Scott is an award-winning Caribbean novelist and short-story writer from Trinidad & Tobago whose second novel Aelred’s Sin was awarded the 1999 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize Best Book in the Caribbean and Canada. His most recent books include the stories Leaving by Plane Swimming Back Underwater (2015) and a new edition of his first novel Witchbroom (2017) – both published by Papillote Press. He was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2019 and divides his time between London and Trinidad. He can be found at www.lawrencescott.co.uk