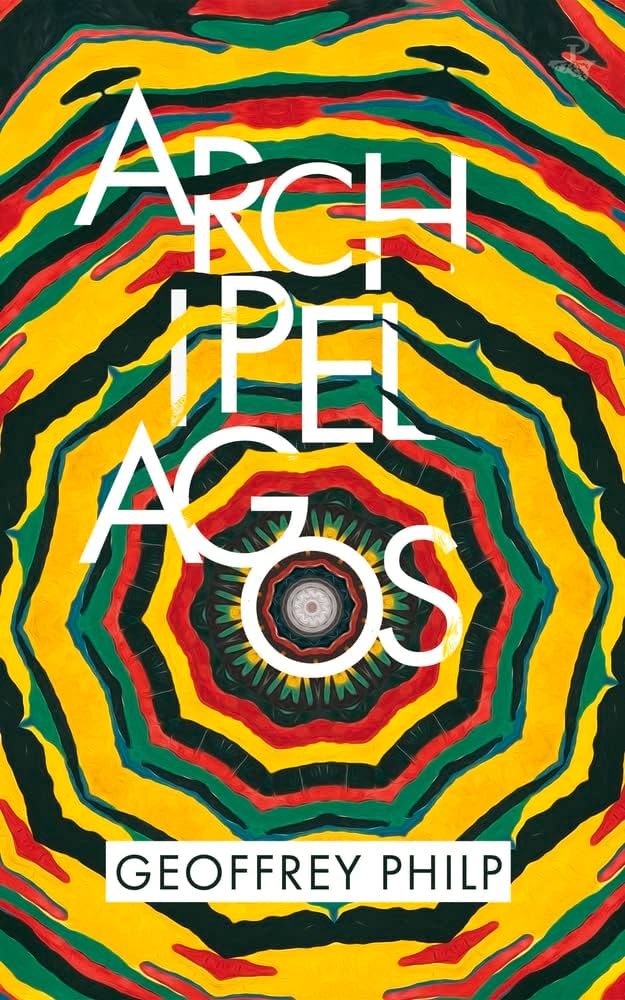

Archipelagos by Geoffrey Philp

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 9781845235505, 62pp)

Poetry tells the world what a poet is thinking and what a society is feeling and/or hiding. Thus, it is often difficult to separate a poet’s thoughts from the reality within which they live, the politics to which they subscribe, and the mundane things that make them passionate agents of change. Audre Lorde, in The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, agrees with this: “poetry is not only dream and vision. It lays the foundations for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.” Geoffrey Philp’s poetry achieves precisely what Lorde described.

Philp, who has authored seven poetry collections including 2010’s Dubwise (Peepal Tree Press), has been a mainstay on the Caribbean literary scene for several decades, with most of his published work being poetry. Archipelagos is his latest offering to the ever-expanding, but highly revered catalogue of Caribbean literature. The collection is as exquisitely accomplished as it is overtly political. Philp stridently adds his voice to the burning issues of colonialism, neo-colonialism, climate change, and social justice in a beautiful flow of verse. Students of intersectionality theory will appreciate this work, especially since Philp establishes clear, logical connections between the issues of colonial oppression based on ethnicity and race, and the current state of class and race relations in the United States of America, and the Caribbean. He also skillfully emphasises the link between colonialism and climate change. ‘Oya Awakened’, an anaphoric sequence that focuses on Hurricane Irma, is one such example: “winds howled through our shutters/ like the wails of Africans trapped/ in the hold of slavers that followed/ the same route as these hurricanes.” Increasingly, and frustratingly, these connections are seldom admitted outside of academic circles, but Philp brings them home in this collection, which is accessible to all readers.

Archipelagos rallies us to speak, and to speak loudly.

From the outset, Philp takes inspiration from Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism as he scans history’s pages for colonisers and tyrants, from Columbus to Leopold II to Hitler. His own discourse on colonialism beautifully sets the stage for the collection’s transition to a focus on the impacts of climate change on the archipelagos of the Caribbean basin as he shows us the interconnectedness of global horrors. In so doing, Archipelagos, which is dedicated to Jamaican writer and environmental activist Diana McCaulay, juxtaposes the disasters of colonialism (in its various incarnations) and climate change with the resilience of landscapes under threat. Moreover, the use of imagery of battered trees and turkey buzzards to represent the re-emergence of life after brutal destruction by natural disasters is poignant for reasons I hope other readers will also see. In ‘Haikus for the End of the World’, there are images of crows and homeless men in circumstances similar to those seen post-hurricane: desolate and bare, exposed to one’s rudiments. Philp clearly wants us to see that beneath the layers of destruction and disaster, regardless of their origins, lies a commonality: human impact. King Austin in his seminal Calypso Progress’ identified as much: “simply because in its quest for success/ nothing stands in man’s way/ old rivers run dry, soon the birds wouldn’t fly.” Philp, cognisant of the devastating impacts climate change will continue to have globally if we do not take action, looks to the future with the warning that climate change “melts ice caps and releases viruses to plague/ future generations, who will live in perpetual fear/ of the next hurricane, heatwaves that disrupt power/ grids, melt electric cables, will fresh air still be free?”

Archipelagos offers the reader both the historical and contemporary perspective, laying bare the issues of different generations while also establishing the link between these issues with tremendous ease and poetic curiosity. Philp criticises the climate of hatred and racism in the United States of America when he first arrives to undertake a fellowship, but he is also aware of and equally horrified at the state of this climate in ‘America 2020’. The rebuke is strong as Philp outlines the migrant crisis, racial killings, gentrification and the ongoing struggle for justice: “America, you’ve lost your way”.

I started by stating poetry tells the world what a society feels and/or hides. It is significant that Philp addresses the issues that he does since we often hide the realities that we are afraid of confronting. We know that they haunt and threaten our existence, but as long as they remain in the shadows and out of our daily conversations, we are not forced to rectify them. The problem with hiding the problems we face is that they do not diminish or disappear over time. A fire in an abandoned house in the middle of nowhere is still a fire with potential to spread. Conversations on colonialism, climate change and social justice too often remain largely within think tanks and talking shops. We avoid these issues because we think that they do not directly affect us or because we are afraid of dealing with the trauma that comes with exposing the raw sores that can be our realities. In the Caribbean, particularly, we exist within a cauldron where colonialism, climate change and issues of social justice concomitantly impact our lives. However, we are yet to have comprehensive discussions on the trauma we inherited from our colonial past and the damage we suffer from climate change, exacerbated by global greenhouse gas emissions we contribute very little to. Philp reminds us that the winds that aided the Middle Passage have now become the hurricanes that threaten the remnants of colonialism in the “archipelago of the dispossessed.” We certainly feel this reality and I do not think we can hide it any longer. Archipelagos rallies us to speak, and to speak loudly.

∞

Rol-J Williams is a poet, bibliophile, medical student from St Kitts and Nevis. He is the moderator of the Caribbean Book Club, which meets monthly to champion regional writing.