There are too many wrong countries in the world.

—Nicholas Laughlin, “Je Vous Écris du Bout du Monde”

1968—that year this world decided to burn down—Mr. Ganesha Amata returned to Guyana from California with a first degree in Education from a university named Berkeley. Michaelmas, 1974: Leela Persaud entered his English Literature class. She was determined not to be foolish like the other girls. Lena Horne taught her grace. Nina Simone, restraint. Queen Aretha, R-E-S-P-E-C-T (demanded when bestowed). The saddest move a woman could make, her mummy taught her, was to bow down to any man before you read him.

“I mean: he dat handsome?” Leela asked Blessing Prosper at lunch.

Blessing set down her sandwich—marmalade between plait bread speckled with star anise—and assumed the posture of a reverend.

“Sister,” Blessing said, palms raised to Black Jesus. “Dat’s how you know if a fella groovy: you try to convince yuhself he not so-so groovy. Go home, baby. Check yuh eyes, nuh?”

Leela mentioned Mr. Amata’s most visible flaw: a gash on his forehead the shape of Cuba, but what did it matter? True-true thing: those eyes were ocean, ocean eyes from a Portuguese father, Mr. Amata’s mother some coolie woman, skin as sapodilla as theirs, they cursed, secretly, for something as lovely as Love.

After those ocean eyes, all those fifteen-year-old girls must have loved Mr. Amata because he had been to America. And not just New York City—not just Brooklyn, man—but California (!), where Lena made the movies, where Nina sang, where the real Queen, God save Aretha, reminded you God was fundamentally sound. Dig: America made Mr. Amata different. You go someplace; it could make you different. For forever. Like you can’t unsee what you know you saw. Not his voice, its register; that stayed the same. He spoke like any Georgetown boy from the kinda family with a piano in the front parlor. But something about the way he swaggered. Like he was in no rush. Like even if Blessing’s Black Jesus—on one hand urging this world to “stir it up,” on the other hand to “simmer down”—were to descend from heaven on any ordinary Thursday, Mr. Amata wouldn’t be harried; he’d keep the same pace.

“Sir? May I ask you a question?” Leela asked Mr. Amata two months into the term. He never ate lunch. Not during the lunch break, at least. He invited his students to talk to him. Like they were comrades. Always that mysterious pile of books on his desk.

“I was never knighted,” Mr. Amata said. “Even if I were, I have very little interest in knights. Mr. Mr. is fine. And, yes, young lady. I’m a great lover of questions.”

“It’s why you come back, eh?” Leela asked.

Leela’s friends, Anand Sukraj and Tulsi Ramkissoon—two boys raised, like her, on the madcap sermons of Pandit Brahma Latchman—stood by her side. Guardsmen in training. Tulsi returned a book by some fella named Seneca to the top of the heap.

“Why do you think I came back?” Mr. Amata asked.

They were all still like the river between question and answer. Mr. Amata placed his long fingers on the tower of books:

Epitaph for the Young by Derek Walcott

Minty Alley by C.L.R. James

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rodney

Miguel Street by V.S. Naipaul

El reino de este mundo by Alejo Carpentier

When Mr. Amata launched into his sermon involving the philosophies of a fella named Frantz Fanon, it became clear, instantly, why fifteen fifteen-year-old girls were willing to exchange an appendage for Mr. Amata’s attention. Something about the way he preached. Pandit Brahma said you knew a man’s intentions from the music of his words.

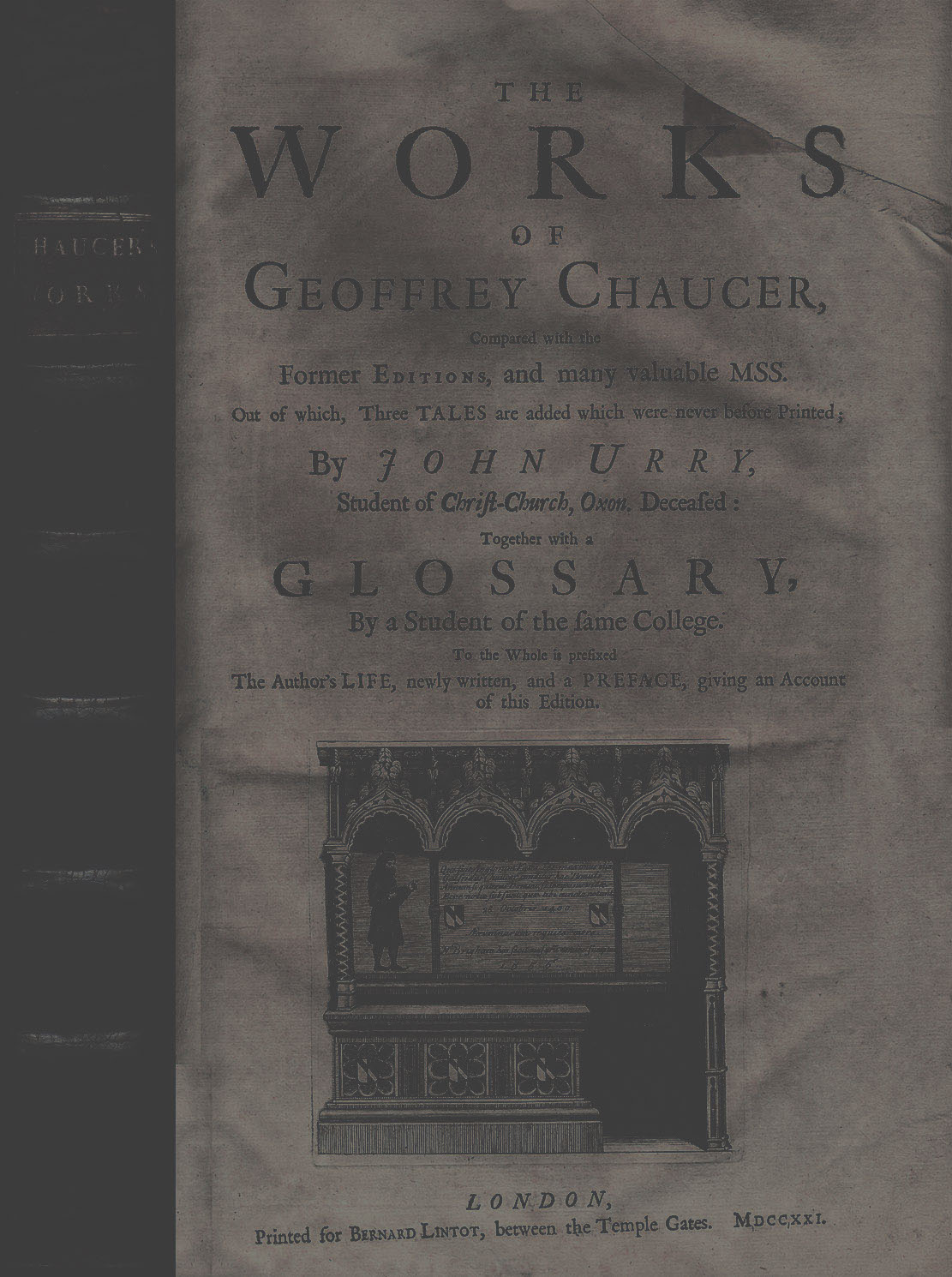

Back then, Leela stuttered. One morning, late November, the students took turns reading stories from The Canterbury Tales, a book about a bunch of folks journeying to some church, telling stories—gossip, really—to pass the time. One story was from a monk. Fragments. Messy. About all these great men who didn’t check their blind spots because they couldn’t fathom they might be blind.

—Lucifer ignoring the pull in his gut: that all his power made his father plot the slyest means to weaken him. Adam putting something tasty in his mouth not knowing how it might end up on the other side. Samson who shoulda met her mummy: the saddest move a man could make was to bow down to any woman before you read her.

When it came time for Leela to read aloud, she told the story of a muscly fella named Hercules:

Was n-n-n-never a man, since this world b-b-b-began

That slew so many m-m-monsters as he did…

Half the class sniffled. Blessing, Anand, and Tulsi: Leela could feel their palms resting on her shoulders though they, her truest friends, were still fidgeting in their seats. Mr. Amata remained Senecan. Cocked his chin toward her book, locked his eyes into hers, and made it clear from his expression that reading a book taught you to choose which sounds you worshipped.

◊

Mr. Amata? What’s a stroke?”

It was three weeks before Christmas. Though she would not be remaining for the rest of the class—the term?, the year?—Leela still wore her uniform, took her time that morning when she pressed the green plaid pleats, the yellow necktie.

The school bell had not yet rung.

7:45, the clock said.

“Blood supply,” he announced, curtly. “Not enough blood to the brain. Brain cells die.”

He looked as if he were mourning those hypothetical brain cells.

“Real serious? Like you can’t never come back good?”

“Young lady, what’s the matter?”

“Mummy,” she said. “My mother.” She corrected herself. She assumed the voice of the journalist, Viola Chambers, she treated like an incarnation of Mother Lakshmi. “My mother had a stroke.”

Mr. Amata squinted academically outside the window though there was nothing urgent to observe. Girls, pencil lead against textbooks, studying what they hadn’t the night before. Two long boys laughing at the sun. Mr. Amata’s reaction reminded her of her mother’s. Like life was about wining around the things you most needed to discuss. When her mother returned from Georgetown Hospital, lying down lost in her bed at six in the afternoon, she appeared like she had committed some sin for falling ill.

“I intend to come back,” Leela said. “Father told the headmaster. But I wished to thank you. In person, sir.”

Leela placed a brick of cassava pone, wrapped neatly in parchment paper, a pink ribbon she borrowed from Mala tied around the package, next to Mr. Amata’s tower of Caribbean literature.

In five minutes, the bell would ring. For the first time, Leela spotted tentativeness in Mr. Amata’s manner. He fumbled in his desk drawer. He removed a stack of papers secured with a blue elastic band. Her essay was at the top—an examination of Miranda’s character in a play called The Tempest by a gentleman known only by his last name. This is how you know you succeeded in the world: people call you by only one name. Like Aretha.

“You’re very bright,” Mr. Amata said, melancholy.

Tick.

Tick.

Tick.

The ticks on her essay resembled incomplete hearts.

“This is what you are capable of when you pay attention to your own mind,” he said. “When you’re not focused on some crowd.”

He was attempting to modulate the stoicism in his voice, which is frequently an act of hypocrisy. Heat and panic fuel the core of this earth.

“Spectacular,” Mr. Amata said. “Your work is spectacular,” he repeated, his face softening.

Spectacular, she whispered, and the word made her think of the fat bear on the flag of California she discovered in Mr Amata’s well-dog-eared Encyclopedia Britannica.

◊

A photograph of Viola Chambers had appeared in a June 1972 profile in the Guyana Standard, a newspaper run by the government, which meant you could trust the news as much as you could trust Neighbor Becca, the Jehovah’s Witness next door who argued that 144,000 people were gonna gain admission to heaven. Neighbor Becca (pretty, frocks floral) bewildered Leela. Who could believe such a cruel lie concerning the destination of all this pushing, eh? Leela had taken her time cutting the photograph of Viola Chambers out of the newspaper. She tacked it on the wall above her writing desk next to an idol of Lord Ganesha and a photograph of her four sisters playing the fool on 63 Beach.

A week before Christmas, Leela was hanging the sheets to dry on the clothesline, which she fancied doing at noon, the sun furious, her sisters at school. Across the fence, she saw a long, patient figure ambling down the road with a stack of books in his hands.

“Hear me: I need you to keep reading,” Mr. Amata said when Leela greeted him.

Leela was uncertain whether he’d even given her a proper introduction.

“The important part—remember this: you have to learn these lines. When you’re doing your chores,” he said, cocking his chin toward the damp pillowcase draped over her shoulder. “I need you to recite these poems. In your mind.”

Mr. Amata left like he appeared. Like he were a specter, a word Leela fancied because she imagined these were the sorts of words Viola Chambers—born in Trinidad, educated at Girton College, Cambridge, a foreign affairs correspondent for the BBC (!)—might use while cutting her meat into tiny, symmetrical pieces or stroking the long stem of her wineglass. She was surprised by the books Mr. Amata brought her. No comrade stargazers.

Chaucer.

Coleridge.

Keats.

Not all white people are made the same, she had concluded. What does it mean to live by a contract you never signed? White people could throw you on a slave boat and write an “Ode to a Nightingale.” This world, man, was funky. The Dictator—black—spoke like he could put his own brother on a slave ship if he had the power. It was dubious whether he gave one flying rass about birdsong.

The callaloo, the sada roti, the pumpkin: all cooling beneath a blood-red gingham veil. Her sisters would return from school in two hours. Her father would soon return from the mechanics’ shop, motor oil beneath trimmed fingernails. Mr. McCarthy had given him his holiday advance early, but he still went into work, kissed her forehead, told her he couldn’t bring home the money had she not filled shoes too big for her feet. Fortune granted Leela forty-five minutes when she could listen to Viola Chambers’ afternoon report in total peace. She laughed at herself, how excited she became to tune the radio to the right frequency. How her heart palpitated when she imagined, one day, standing between an event and its message. Viola Chambers reported the mad things stoically: people in Ireland bombing English pubs because energy cannot be destroyed, only transformed. She reported the light things casually: China donated two pandas named Ching-Ching and Chia-Chia to Britain in a gesture of goodwill. She reported the bad news coldly: inflation, 17.2%. She reported the good news triumphantly: some Austrian man shares the Nobel Prize with his rival—a Swede named Gunnar—for some innovation where one layer folds into the next.

Her mummy was never skinny, but she was growing bigger those months and feeling bad about it, her face constantly concealing some worry she tried to mask with a sudden, insincere smile when she caught Leela watching her through the sides of her eyes.

“Sweetness!” Leela said, catcalling.

She set down the glass of sorrel, scarlet as a hemorrhage, that she prayed might replace the blood required to supply her mummy’s brain.

“Me? Look how I getting sluggish lying down whole day while you ah wuk like engine.”

Her mummy was beginning to put her words together again more fluidly. Whenever she faltered, Leela decided God was teaching them to listen to their meanings more carefully.

Leela uncorked the Limacol, lemons and alcohol perfuming the bedroom. She parted her mummy’s hair, soaked a handkerchief, and pressed it against her forehead. Leela summoned Viola Chambers’ murti.

“Mummy, you wanna hear a story bout dis fella name Hercules?”

“Wha?”

“Dis fella…”

“I know who Hercules is…”

“You wanna hear he story?”

“Make it good, baby,” she said.

Leela became Viola Chambers.

Was never a man, she started, as high-class as she could manage, since this old world began

That slew so many monsters as did he.

Through all earth’s wide realms his honor ran

What of his strength and high chivalry…

By January 1975, Leela could recite all six stanzas the monk devoted to Hercules’ tale—not a single stutter.

“How was dat, mummy?” Leela asked when she was finished.

Leela removed the handkerchief from her mummy’s mind, corked back the bottle of Limacol.

“Baby, I learn life short: I can be honest?”

“Only way.”

“Baby, you sound like a chicken right before he get ready fuh dead.”

◊

Her mummy laughed, water collecting at the edges of her eyes, and so did she. This is love: accepting you’re at the end of the joke when the joke is the revelation of the truth. When Leela worried with the crowd, she stuttered. When she thought she traveled deeply into her soul, she couldn’t fathom her blind spot: she hadn’t traveled deeply enough. What she’d done was stolen another woman’s voice.

February 1975, it became clear her mummy was going to be fine. Look at her, Leela thought: strutting around the house, inspecting each piece of furniture like a physicist. Kissing her teeth when she noticed a greenheart cabinet went unpolished, that dust was collecting beneath a doily.

Laziness! Me steadysteady ah say: it’s how you do de small tings, just so you gonna do de big tings, nuh? But dem pickney done get P, H, D.

She curried crab. Fried dumplings. Invited Neighbor Becca to provide a brief history of the many months of story she had missed.

The family wished to offer gratitude to Lord Ganesha. Pandit Brahma insisted they celebrate. Pandit Brahma: Jesus, what a strange concoction of a man! Leela imagined if he traveled to India—to some temple in Varanasi, to some river in Vrindavan—devotees would not quite know what to do with him. Because Pandit Brahma was like her: twenty thousand voices in subtle competition. They mixed them, loved them, left them in a manner that felt sometimes harsh, but mostly sincere. Pandit Brahma was a great lover of James Brown, who he argued was quite Hindu. How, pray tell me, does a chant change this funkyfunky world?

Truth be told, however, Leela possessed limited patience for Pandit Brahma’s ecstasies. She still loved Viola Chambers’ reserve. Pandit Brahma’s sideroads and digressions: how she wished the man would make an appointment with Aristotle. But she loved him, and he loved her like friends born to disagree.

“Walk with me,” he once told her. “Shall I tell you a story? Do you know how Ganesha wrote the Mahabarata? Well, I think it went something like this. But I cannot tell you for certain, daughter. See? I was not there. So here is my first rule: be careful about what you say if you were not there. Fair?”

“Like law.”

“Lovely. Ganesha challenged the dictator—the dictator as in he who tells the story. Ganesha told the dictator—his name was Vyasa—that I will write your story on one condition: you must tell your story without a pause. Vyasa, well, love, he must have gotten nervous: what does it mean when words spill like a waterfall? Vyasa counters. Tells Ganesha the only way their partnership could work is if He understands every verse before writing it.”

This is what she tried to do at her desk late at night when her mummy and her daddy and Mala and Kamla and Devi and Rohini were snoring softly, dancing in their own world of dreams. She kept a notebook she filled for nobody: she simply had to. The evening, late in April, 1975, when she was preparing to return to school, she decided to offer gratitude to Mr. Ganesha Amata, something more meaningful than cassava pone. She wanted him to know—really know—that what he was doing was important and lovely, that to this funkyfunky world, it might seem he was just a teacher—nobody—when what he was doing was changing how they breathed.

Leela opened Chaucer, sharpened her pencil, lit the kerosene flame. The pencil danced against the notebook without her doing, the sound like wind against the fronds of a palm.

Never was a fella since dis funkyfunky world began, she translated

That mash up so much jumbie so

From Guyana to the Bahamas, word spread

Bout how he don’t take stchupidness from no man,

The kinda scamp who want you look left

When you know right is Right.

Grow strong on roti and callaloo

Okra, steam fish.

Know which sounds to surrender,

Which to defend.

Never trust a kingdom; God, how they’ll fail you.

Most of all, remember dis:

Never bow down to any man before you read him.

∞

Stephen Narain is a writer and teacher based in Orlando, Florida, the winner of 2020’s Bristol Short Story Prize. He was raised in the Bahamas by Guyanese parents, has an MFA in Fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has won the Small Axe Fiction Prize and the Alice Yard Prize for Art Writing.